|

|

|

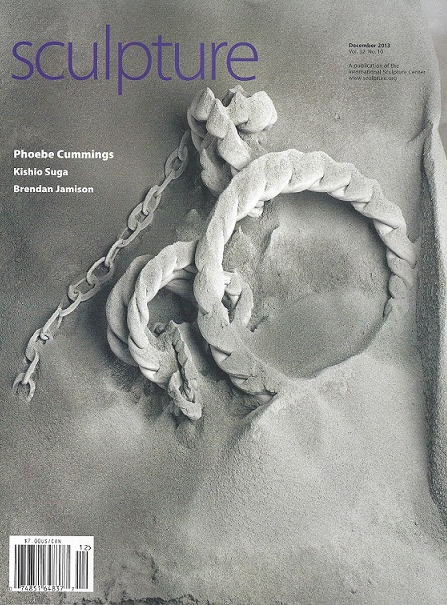

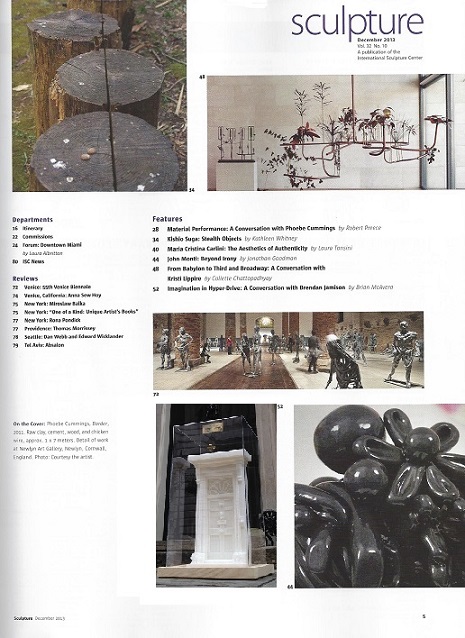

SCULPTURE magazine: December 2013, Vol. 32, No. 10

Published by the International Sculpture Center, New Jersey, USA

Digital edition:

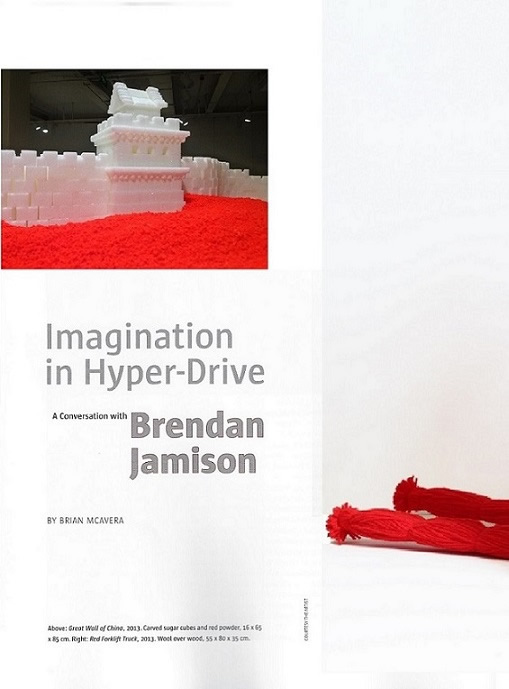

Imagination in Hyper-Drive

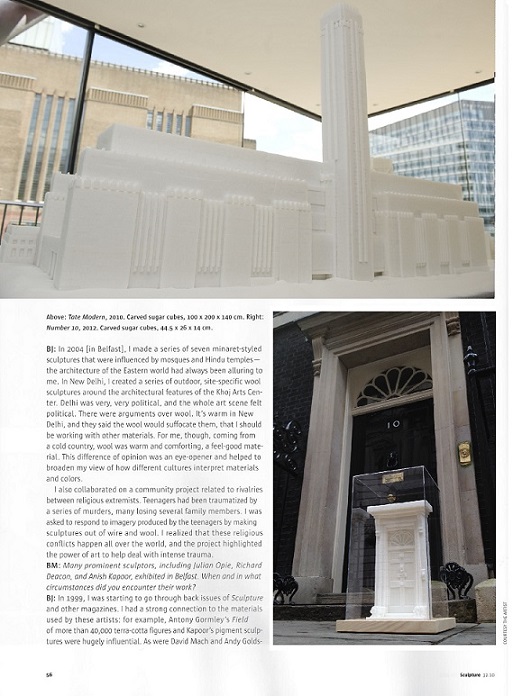

A conversation with Brendan Jamison BY BRIAN MCAVERA It's rare for Irish sculptors, particularly those from Northern Ireland, to have a high profile by the time they are in their early 30s, but Brendan Jamison, seemingly without effort, has propelled himself into the limelight and is unlikely to be dislodged in the near future. I say "seemingly" because Jamison makes everything look easy, which is, of course, the mark of the true professional. In fact, he is a meticulously hard worker and an unusually gifted artist who uses non-traditional sculptural materials. Over the past decade, he has shown across three continents, and he has a "nose" for the high profile, such as his sugar-cube sculptures of the Tate Gallery and No. 10 Downing Street (exhibited at that building). Jamison is quirky and shrewd - one of those rare sculptors whose work has a quiet sense of humor. He has also, unlike so many Irish male sculptors, managed to avoid the trap of an insistently phallic machismo. Jamison integrates his male and female selves. Watching his sculptural mutations is one of the pleasures of a critic's life.

Full interview available in print copy of the magazine

McAVERA, BRIAN. "Imagination in Hyper-Drive: A conversation with Brendan Jamison", SCULPTURE, International Sculpture Center, New Jersey, December 2013, Vol. 32 No. 10, pp. 1, 5, 52-59. ISSN 0889-728X |

___________

MAY 2011

Detail: Brendan Jamison, Tate Modern & NEO Bankside, 2010. Carved sugar cubes and loose sugar crystals, installation of 5 architectural models, 100 x 347.5 x 180 cms Neo Bankside, designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners, is a new residential development adjacent to Tate Modern on the South Bank of London. As a contribution to the London Festival of Architecture (and a rather astute PR exercise), developers Native Land and Grosvenor commissioned Irish sculptor Brendan Jamison to re-create both buildings as 1:100 scale models made entirely of sugar cubes. These are not small models. The chimney of the Tate building stands over a meter high. Jamison used over 22.5 liters of glue and 80,000 sugar cubes just in this one model, which weighs more than 255 kilos. Of the four pavilions that make up the Neo Bankside development, two are 12 stories high, one 18 stories, and the last, which rises 24 stories, is rendered complete with crane. Sculptors have happily used a wide range of materials since the beginning of the 20th century, though sugar can hardly be considered a popular choice. The statistics reflect the painstaking nature of Jamison's enterprise; the material, however, indicates a sculptor unusually alert to the resonances and associations of non-traditional materials. As with his previous use of wool, or indeed his previous use of sugar cubes, what he effects--which the poet and novelist Robert Graves would immediately have recognized--is an amalgam of the masculine and the feminine. But it is put to a masculine use; constructed into the instantly recognizable towering mass of Tate Modern or engineered into the phaliocentric verticals of the pavilion towers. While Jamison’s earlier sugar sculptures tempered masculine verticality with a soft opening at the top (like a blossoming flower), the feminine dimension of these works is more subtly modulated into sugar itself. In a sense, the sculptures have become androgynous. With the Tate, he does the impossible, amply suggesting the weight and mass of the building [its three-dimensional quality reinforced by the use of cast shadow), together with its almost oppressively dark presence, while holding these male qualities in a suspension through the whiteness of the sugar and its sparkling, reflective qualities. One strange effect of using sugar is that the articulation of the Tate becomes more overt than in real life, the model has a fluidity and decorative quality absent in the original. In the pavilion tower blocks, on the other hand, sugar masks the transparency of the see-through glass while, paradoxically, substituting its sparkle for absent light. According to Jamison, carving sugar cubes is quite difficult. What might look like an exercise in Lego building is rather more complicated. The scale of the project required him to use different brands, and he found, to his consternation, that they were not all the same size, and some were more responsive to carving than others. There is an ordinariness about sugar cubes, an everyday domesticity and suggestion of childhood that is very appealing. There is also the underlying suggestion of mythic and fairy-tale elements. It's as if these serried ranks of cubes become a tabula rasa on which we can project our own thoughts and dreams. In a way, it's a bit like watching Clint Eastwood. Little seems to happen on his face, yet we read into it a world of repressed emotion. Jamison really is a sculptor to watch--not yet 30, he has already developed a number of distinct and separate modes of working, and in each one, he is quietly developing and expanding his vocabulary. Like the young Calder, he is also, surprisingly, a crowd-pleaser as well. Brian McAvera

McAVERA, BRIAN. "Reviews: London: Brendan Jamison", SCULPTURE, International Sculpture Center, New Jersey, May 2011, Vol. 30 No. 4, p 71

_____________________

JULY/AUGUST 2009

JCB BUCKET SERIES (2008) Brendan Jamison, microcrystalline and paraffin wax over wood, 15 sculptures, dimensions ranging from 30 x 20 x 25 cms to 76 x 70 x 58 cms, Queen Street Studios Gallery, Belfast, Northern Ireland

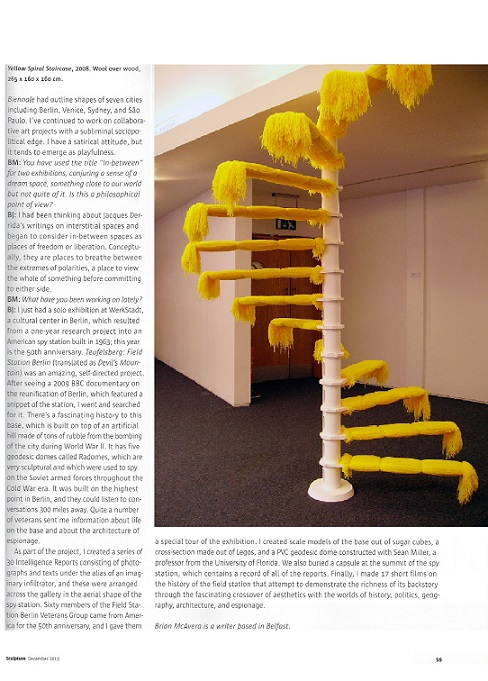

Brendan Jamison is one of a group of younger Northern Irish artists whose works are entirely unmarked by The Troubles. His development has been rapid and engaging. He owes little to the Irish tradition of sculpture, insistently reminding one of the British sculptors of the '80s and '90s such as Richard Deacon, Tony Cragg, Richard Wentworth, and Anish Kapoor. Jamison's affinities with them are marked: playfulness, inventiveness, unusual use of materials, and the drive to generate exhibitions across several continents. In 2001, he was wrapping a tree with multi-colored threads of wool, creating an aura for it, transforming it, and, in effect, dematerializing the object. This notion of transformation continues in his recent work, whether by wrapping, coating in wax, or even creating objects out of sugar cubes. Jamison has stated that his practice "attempts to highlight an in-between state or middle path, a calm place where extremes," such as "organic and architectural, male and female, Eastern and Western...rigid and fluid, sexual and spiritual," can be seen side-by-side or in gentle convergence. Left: RED TUNNEL detail (2008) Brendan Jamison, wool over wood, 12 components, 212 x 500 x 600 cms. Right: DECAYING GREEN JCB BUCKET (model GTHB51) (2008) Brendan Jamison, microcrystalline and paraffin wax over wood, 46 x 42 x 26 cms In the first of his two recent exhibitions, "In-Between", the wrapping element came to the fore. Three large-scale installation pieces, Yellow Spiral Staircase, Red Tunnel, and Blue Bridge, all made out of wood, had been wrapped in brightly colored wool, specially ordered from Tivoli Spinners in Cork. Yellow Spiral Staircase has a strong sense of the playful and humorous. Lacking handrails and ascending from the floor to the ceiling, it is deprived of the normal staircase function, or actually going somewhere. One could imagine this child-dangerous, as opposed to child-friendly, piece being resurrected in another life in a playground for adults. The same slightly joky, slightly surreal ambience pervades Red Tunnel, though this much more ambitious piece taps into archetypal imagery, tribal sculpture, and darker recesses of science fiction. The construction, which echoes womb-like caverns and can be entered, was based on the sci-fi drama Earth: Final Conflict. This description, however, makes Red Tunnel seem more solemn than it is. Unusually, this piece wears its imagery lightly. It's interactive (small children are irresistibly attracted to it), and its feminine elements (the warmth and softness of the wool, the amniotic connotations of the womb) are balanced not only by the male under-pinning of wood, but also by small boys entering the forbidden zone. With the "JCB Bucket Series", Jamison shifts into a different gear. The idea for the exhibition was generated when he was walking around post-conflict Belfast, currently one huge redevelopment site. JCB back-hoes are ubiquitous in a redevelopment area, and what particularly appealed to Jamison were the animal-like qualities of the "head" or bucket when it was "protectively" down, at ground level, at nighttime. The works, initially based on Lego versions of JCB buckets, are made out of microcrystalline and paraffin wax over wood. If one thinks of the sci-fi world of Alien, particularly of the bio-morphic, surreal, and menacing elements, and then introduces a disturbingly playful sense of humor, you get JamisonWorld. With this series, the socio-political elements of regeneration are barely registered. As in classic sci-fi, the world of the inanimate is made animate. "Exuberant" is perhaps too strong a word, but the world of toys, of childhood, of the ogre-ish imaginings of fairy tales is re-animated in these works. The most successful examples are those in which the transformative element dominates. The wax, suggesting stalagmites and stalactites, drips, for example, into fanged incisors. Baby JCBs are birthed and sheltered, kangaroo-style, by the "mother", or the mother form develops a noticeably pregnant swelling. Rigid strata are transformed with wax, transmuted and transposed - the ordinary becomes the extraordinary. It's such a pleasure to welcome a real sculptor who has a deft, playful touch, as well as an over-active imagination. Brian McAvera

McAVERA, BRIAN. "Reviews: Belfast and Portadown, Northern Ireland: Brendan Jamison", SCULPTURE, International Sculpture Center, New Jersey, July/August 2009, Vol. 28 No. 6, pp. 70-71

|